Find shows 4,000-year-old trade routes stretched from Carolinas to Great Lakes

Cremated remains and a copper band suggest far-flung trade and social connections.

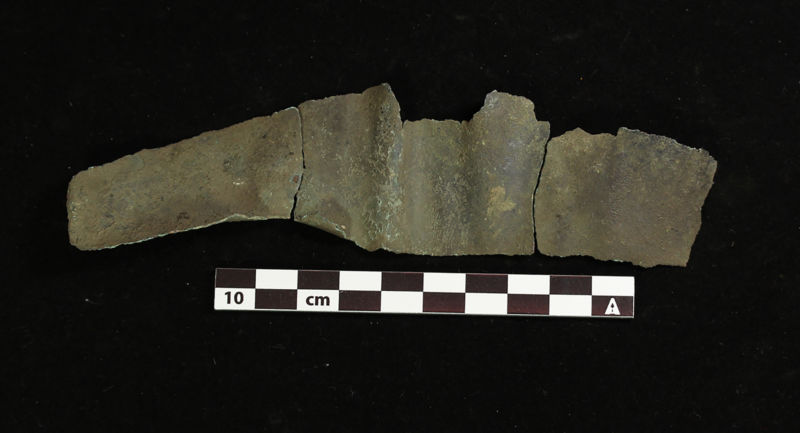

This copper band was interred with the cremated remains of at least seven people.

American Museum of Natural History

Cremated remains and a broken copper band in a 4,000-year-old settlement on a barrier island off the coast of Georgia suggest that trade networks in ancient North America linked people from the Great Lakes to the southeastern coast. And it wasn't just about exchanging goods; the far-flung connections created shared culture.

Widespread trade networks once linked communities in northeastern US with those around the Great Lakes and the Ohio River Valley and extended south to the Tennessee River Valley. Around 5,000 years ago, hunter-gatherer societies in eastern North America started to become more settled, and their populations started to grow. As these communities grew, they also developed long-distance social and economic connections with other communities.

In the archaeological record, we can only really see evidence for the exchange of goods, especially shells, beads, raw stone for working into tools, and copper. But those are probably just the tangible pieces of a more complex set of relationships that may have included political marriages to cement alliances and large ritual gatherings to bring people together and demonstrate wealth, power, and status.

Out of the loop

"Other social practices also travelled along trade routes," wrote Binghamton University archaeologist Matthew Sanger and his colleagues. One of those was the practice of cremating the dead, which shows up, along with copper grave goods, at sites from the Great Lakes to Tennessee. That implies, to some extent, that people spread across hundreds of miles had come to share some common beliefs about proper treatment of the dead—and probably other aspects of life, too.

But for a long time, it has looked like coastal communities in what is now the southeastern US were left out of that loop. Around the same time that societies farther north and inland were settling down and forming social and political networks, people on the southeastern coast were heaping shells into broad rings around open plazas, some as wide as 650 feet. These shell walls reached several yards high, and radiocarbon dating suggests they took centuries to accumulate. We know of more than 50 of these shell rings, scattered along the Gulf and Atlantic coastlines from South Carolina to Mississippi.

There's evidence that people lived at these sites year-round, probably in villages of several family groups, and it's clear that they ate a lot of shellfish—mostly oyster, with some clam and mussel mixed in. But the shell ring builders themselves are something of an enigma, because we've never found an actual grave associated with these sites.

Many archaeologists have assumed that the builders were simple hunter-gatherer societies, living in provincial backwater settlements disconnected from the wider trade networks. One reason for that assumption is that archaeologists have never found copper at a coastal site from this period, except at the huge earthen mound complex at Poverty Point, Louisiana. But that's not surprising; Poverty Point was a major trade hub and ritual gathering center. And we don't have any evidence that people in the Southeast cremated their dead, either.

A shared grave and an exotic artifact

On St. Catherine's Island in Georgia, in the very center of the 98- to 131-foot-wide McQueen Shell Ring, Sanger and his colleagues found a small burial pit containing the burned, crushed bones of seven people. They were mingled with animal remains, stone tools, and a broken copper band. It looks like the kind of burial—and the kind of artifact—that belongs much farther to the northwest, not on the Georgia Coast. The surprising find links the ring builders to the wider network of trade and cultural exchange on the mainland.

The gray, white, and blue-white surfaces of the bone fragments reveal exposure to extreme heat, somewhere between 932º and 1,652º Fahrenheit. All seven people had been cremated, and the larger pieces of bone that remained after burning had been crushed into smaller fragments, although a few larger pieces remained, allowing archaeologists to determine the ages and sexes of the dead.

One woman's remains lay alone in a lower layer of the pit; signs of trauma and infection marked the surviving fragment of her radius, suggesting that she may have died from a wound that became infected. In a layer just above her rested the cremated remains of at least six other people: five adults (a group that included both males and females) and one child. Radiometric dating puts the burial at 4,100 to 3,980 years old, the same age as the shell ring itself.

Among the bones, archaeologists found a copper band, broken and incomplete, and a few copper fragments nearby. The band had been shaped and flattened to 0.75 to 1.5 inches wide and just 0.03 inches thick but bore no engravings or other decoration.

Sanger and his colleagues compared the chemical composition of the copper with samples of copper sources from around the eastern US, and the closest match they found was with the Minong Mine on Isle Royale on the north side of Lake Superior, where people first mined copper with stone tools 4,500 years ago.

"This is surprising since the McQueen Shell Ring is located closer to native copper sources in the southern Appalachians (roughly 480 km) and much farther from sources in the Great Lakes (roughly 1,850 km)," wrote the archaeologists. That, they claim, is clear evidence that people at McQueen Shell Ring on the seaward side of a low-lying island were part of a long-distance network of trade and cultural exchange that stretched all the way to the Great Lakes. And the cremation shows that people were exchanging not just exotic trade goods, but also ideas, beliefs, and social systems.

Pomp and circumstance

The cremated bones and the single copper band mean that ancient trade networks were more extensive than archaeologists realized, but they also suggest that the ring builders lived in more complex societies than anyone expected. Exotic goods like copper from distant mines would have given a rising class of social elites a tangible claim to status, especially if they could control the distribution of those goods. In other cultures, the upper class gives away such items, along with stockpiles of food, at large ritual gatherings where they can curry favor and demonstrate their power.

"The discovery of exotic copper in the center of the McQueen Shell Ring is the strongest evidence that long-distance exchange networks connected ring builders to distant neighbors and that power imbalances were emerging and solidifying in the shell rings," Sanger and his colleagues wrote.

In the case of the shell ring settlements, archaeologists think people hosted seasonal gatherings, probably during the winter months, which may have included shellfish feasts along with rituals of some sort, although we can't know for sure.

None of the dead was wearing the band when they were cremated; the metal doesn't show any evidence of melting or even discoloration, so it was probably placed in the pit after the cremated remains. People had burned other grave goods with the deceased—animal bones, including whale, deer, and fish, are mingled with the human bone fragments, and stone projectile points in the pit are discolored from the heat of the fire. But the copper band, an item brought from a thousand miles away, was placed in the pit afterward, which suggests a significant moment.

"This object was purposefully taken out of circulation, likely during a very visible event in which human bodies were burned, pulverized, and then emplaced in the ring center," Sanger and his colleagues wrote. But we'll probably never know exactly why the people at McQueen Shell Ring placed a single copper band in a grave shared by seven people or what the moment meant to the community. The burial itself almost leaves us with more questions than answers.

"We know little about who these individuals were, why they were buried together, and why they were interred in the ring center along with the copper object and other potent items, including a whale vertebra," Sanger and his colleagues wrote. There's not enough evidence at the site to draw firm conclusions about how the people buried in the center of the ring plaza died, whether they were related, or even whether the six people in the upper burial were all interred at the same time.

Perhaps the people in the burial pit held high rank in the community, and this prominent burial was an honor. Maybe their interment was part of a larger religious ceremony; in their paper, Sanger and his colleagues discreetly suggested the possibility of sacrifice, but there's no more evidence for that scenario than any other. The reverse could also be true—maybe this interment, surrounded by valuable grave goods in the center of the plaza, was a way to appease the spirits of people who died of disease or accident. The people in the grave may even have been from the Great Lakes themselves, buried according to their own customs.

All of the potential stories are compelling in their own ways, but for now, archaeologists can only speculate.

PNAS, 2018. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1808819115 (About DOIs).

No comments:

Post a Comment