Mojoprofessor

Tuesday, February 26, 2019

Thursday, August 16, 2018

Evidence of early native American parrot breeding - Archaeology

Thursday, August 2, 2018

Find shows 4,000-year-old trade routes stretched from Carolinas to Great Lakes | Ars Technica

Find shows 4,000-year-old trade routes stretched from Carolinas to Great Lakes

Cremated remains and a copper band suggest far-flung trade and social connections.

by Kiona N. Smith - Jul 31, 2018 8:45am PDT

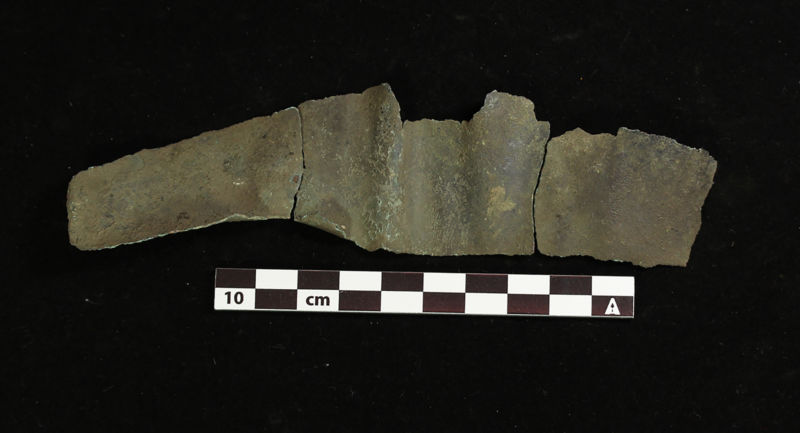

This copper band was interred with the cremated remains of at least seven people.

American Museum of Natural History

Cremated remains and a broken copper band in a 4,000-year-old settlement on a barrier island off the coast of Georgia suggest that trade networks in ancient North America linked people from the Great Lakes to the southeastern coast. And it wasn't just about exchanging goods; the far-flung connections created shared culture.

Widespread trade networks once linked communities in northeastern US with those around the Great Lakes and the Ohio River Valley and extended south to the Tennessee River Valley. Around 5,000 years ago, hunter-gatherer societies in eastern North America started to become more settled, and their populations started to grow. As these communities grew, they also developed long-distance social and economic connections with other communities.

In the archaeological record, we can only really see evidence for the exchange of goods, especially shells, beads, raw stone for working into tools, and copper. But those are probably just the tangible pieces of a more complex set of relationships that may have included political marriages to cement alliances and large ritual gatherings to bring people together and demonstrate wealth, power, and status.

Out of the loop

"Other social practices also travelled along trade routes," wrote Binghamton University archaeologist Matthew Sanger and his colleagues. One of those was the practice of cremating the dead, which shows up, along with copper grave goods, at sites from the Great Lakes to Tennessee. That implies, to some extent, that people spread across hundreds of miles had come to share some common beliefs about proper treatment of the dead—and probably other aspects of life, too.

But for a long time, it has looked like coastal communities in what is now the southeastern US were left out of that loop. Around the same time that societies farther north and inland were settling down and forming social and political networks, people on the southeastern coast were heaping shells into broad rings around open plazas, some as wide as 650 feet. These shell walls reached several yards high, and radiocarbon dating suggests they took centuries to accumulate. We know of more than 50 of these shell rings, scattered along the Gulf and Atlantic coastlines from South Carolina to Mississippi.

There's evidence that people lived at these sites year-round, probably in villages of several family groups, and it's clear that they ate a lot of shellfish—mostly oyster, with some clam and mussel mixed in. But the shell ring builders themselves are something of an enigma, because we've never found an actual grave associated with these sites.

Many archaeologists have assumed that the builders were simple hunter-gatherer societies, living in provincial backwater settlements disconnected from the wider trade networks. One reason for that assumption is that archaeologists have never found copper at a coastal site from this period, except at the huge earthen mound complex at Poverty Point, Louisiana. But that's not surprising; Poverty Point was a major trade hub and ritual gathering center. And we don't have any evidence that people in the Southeast cremated their dead, either.

A shared grave and an exotic artifact

On St. Catherine's Island in Georgia, in the very center of the 98- to 131-foot-wide McQueen Shell Ring, Sanger and his colleagues found a small burial pit containing the burned, crushed bones of seven people. They were mingled with animal remains, stone tools, and a broken copper band. It looks like the kind of burial—and the kind of artifact—that belongs much farther to the northwest, not on the Georgia Coast. The surprising find links the ring builders to the wider network of trade and cultural exchange on the mainland.

The gray, white, and blue-white surfaces of the bone fragments reveal exposure to extreme heat, somewhere between 932º and 1,652º Fahrenheit. All seven people had been cremated, and the larger pieces of bone that remained after burning had been crushed into smaller fragments, although a few larger pieces remained, allowing archaeologists to determine the ages and sexes of the dead.

One woman's remains lay alone in a lower layer of the pit; signs of trauma and infection marked the surviving fragment of her radius, suggesting that she may have died from a wound that became infected. In a layer just above her rested the cremated remains of at least six other people: five adults (a group that included both males and females) and one child. Radiometric dating puts the burial at 4,100 to 3,980 years old, the same age as the shell ring itself.

Among the bones, archaeologists found a copper band, broken and incomplete, and a few copper fragments nearby. The band had been shaped and flattened to 0.75 to 1.5 inches wide and just 0.03 inches thick but bore no engravings or other decoration.

Sanger and his colleagues compared the chemical composition of the copper with samples of copper sources from around the eastern US, and the closest match they found was with the Minong Mine on Isle Royale on the north side of Lake Superior, where people first mined copper with stone tools 4,500 years ago.

"This is surprising since the McQueen Shell Ring is located closer to native copper sources in the southern Appalachians (roughly 480 km) and much farther from sources in the Great Lakes (roughly 1,850 km)," wrote the archaeologists. That, they claim, is clear evidence that people at McQueen Shell Ring on the seaward side of a low-lying island were part of a long-distance network of trade and cultural exchange that stretched all the way to the Great Lakes. And the cremation shows that people were exchanging not just exotic trade goods, but also ideas, beliefs, and social systems.

Pomp and circumstance

The cremated bones and the single copper band mean that ancient trade networks were more extensive than archaeologists realized, but they also suggest that the ring builders lived in more complex societies than anyone expected. Exotic goods like copper from distant mines would have given a rising class of social elites a tangible claim to status, especially if they could control the distribution of those goods. In other cultures, the upper class gives away such items, along with stockpiles of food, at large ritual gatherings where they can curry favor and demonstrate their power.

"The discovery of exotic copper in the center of the McQueen Shell Ring is the strongest evidence that long-distance exchange networks connected ring builders to distant neighbors and that power imbalances were emerging and solidifying in the shell rings," Sanger and his colleagues wrote.

In the case of the shell ring settlements, archaeologists think people hosted seasonal gatherings, probably during the winter months, which may have included shellfish feasts along with rituals of some sort, although we can't know for sure.

None of the dead was wearing the band when they were cremated; the metal doesn't show any evidence of melting or even discoloration, so it was probably placed in the pit after the cremated remains. People had burned other grave goods with the deceased—animal bones, including whale, deer, and fish, are mingled with the human bone fragments, and stone projectile points in the pit are discolored from the heat of the fire. But the copper band, an item brought from a thousand miles away, was placed in the pit afterward, which suggests a significant moment.

"This object was purposefully taken out of circulation, likely during a very visible event in which human bodies were burned, pulverized, and then emplaced in the ring center," Sanger and his colleagues wrote. But we'll probably never know exactly why the people at McQueen Shell Ring placed a single copper band in a grave shared by seven people or what the moment meant to the community. The burial itself almost leaves us with more questions than answers.

"We know little about who these individuals were, why they were buried together, and why they were interred in the ring center along with the copper object and other potent items, including a whale vertebra," Sanger and his colleagues wrote. There's not enough evidence at the site to draw firm conclusions about how the people buried in the center of the ring plaza died, whether they were related, or even whether the six people in the upper burial were all interred at the same time.

Perhaps the people in the burial pit held high rank in the community, and this prominent burial was an honor. Maybe their interment was part of a larger religious ceremony; in their paper, Sanger and his colleagues discreetly suggested the possibility of sacrifice, but there's no more evidence for that scenario than any other. The reverse could also be true—maybe this interment, surrounded by valuable grave goods in the center of the plaza, was a way to appease the spirits of people who died of disease or accident. The people in the grave may even have been from the Great Lakes themselves, buried according to their own customs.

All of the potential stories are compelling in their own ways, but for now, archaeologists can only speculate.

PNAS, 2018. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1808819115 (About DOIs).

American Fur Company - Wikipedia

American Fur Company

The American Fur Company (AFC) was founded in 1808, by John Jacob Astor, a German immigrant to the United States.[1] During the 18th century, furs had become a major commodity in Europe, and North America became a major supplier. Several British companies, most notably the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company, were eventual competitors against Astor and capitalized on the lucrative trade in furs. Astor capitalized on anti-British sentiments and his commercial strategies to become one of the first trusts in American business and a major competitor to the British commercial dominance in North American fur trade. Expanding into many former British fur-trapping regions and trade routes, the company grew to monopolize the fur trade in the United States by 1830, and became one of the largest and wealthiest businesses in the country.

| |

| Private | |

| Industry | Fur trade |

| Fate | Dissolved |

| Successor | None |

| Founded | New York City, U.S. (1808) |

| Founder | John Jacob Astor |

| Defunct | 1847 |

| Headquarters | New York City |

Area served | United States and Territories |

Astor planned for several companies planned to function across the Great Lakes, the Great Plains and the Oregon Country to gain control of the North American fur trade. Comparatively inexpensive manufactured goods were to be shipped to commercial stations for trade with various Indigenous nations for fur pelts. The sizable number of furs collected were then be brought to the port of Guangzhou, as pelts were in high demand in the Qing Empire. Chinese products were in turn be purchased for resale throughout Europe and the United States. A beneficial agreement with the Russian-American Company was also planned through the regular supply of provisions for posts in Russian America. This was planned in part to prevent the rival Montreal based North West Company (NWC) to gain a presence along the Pacific Coast, a prospect neither Russian colonial authorities or Astor favored.[2]

Demand for furs in Europe began to decline during the early 19th century, leading to the stagnation of the fur trade by the mid-19th century. Astor left his company in 1830, the company declared bankruptcy in 1842, and the American Fur Company ultimately ceased trading in 1847.

BackgroundEdit

OriginEdit

Prior to John Jacob Astor creating his enterprise in the Oregon Country, European descendants throughout previous decades had suggested creating trade stations along the Pacific Coast. Peter Pond, an active American fur trader, offered maps of his explorations in modern Alberta, Saskatchewan and the Northwest Territories to both the United States Congress and to Henry Hamilton, Lieutenant Governor of Quebec in 1785. While it has been conjectured that Pond wanted funding from the Americans to explore the Pacific Coast for the Northwest Passage,[3] there is no documentation of this and it is more likely that he had sent a copy of the map to Congress due to personal pride.[4] Pond later became a founding member of the North West Company (NWC) and continued to trade in modern Alberta.

In time Pond had an influence upon Alexander Mackenzie, who later crossed the North American continent.[4] In 1802, Mackenzie promoted a plan form the "Fishery and Fur Company" to the British Government. In it he called for "a supreme Civil & Military Establishment" on Nootka Island, with two additional posts located on the Columbia River and another in the Alexander Archipelago.[5] Additionally this plan was formed to bypass the three major British monopolies at the time, the Hudson's Bay Company, the South Sea Company and the East India Company for access the Chinese markets.[5] However the British Government ignored the plan, leaving the NWC to pursue MacKenzie's plans alone.[3] Another likely influence upon Astor was a longtime friend, Alexander Henry. At times Henry mused at the potential of the western coast. Forming establishments on the Pacific shoreline to harness the economic potential would be "my favorite plan" as Henry described in a letter to a New York merchant.[6] It is likely that these considerations were discussed with Astor during his visits to Montreal and the Beaver Club. Despite not originating the idea to create a venture on the Pacific coast, Astor's "ability to combine and use the ideas of other men"[6] allowed him to pursue the idea.

China tradeEdit

Astor joined in on two NWC voyages charted to sail to the Qing Dynasty during the 1790s. These were done with American vessels to bypass British commercial law, which at the time prohibited any company besides the British East India Company from commerce with China. These were financially profitable ventures, enough so that Astor offered to become the NWC agent for all shipments of furs destined for Guangzhou. However Alexander Mackenzie denied his offer, making Astor consider financing voyages to China without the Canadian traders.[7] Now a fully independent international merchant, Astor began to fund trading voyages to China along with several partners. Cargoes often amounted to $150,000 in such as otter and beaver pelts, in addition to needed specie. Astor ordered the construction of the Beaver in 1803 to expand his trade fleet.[8]

FormationEdit

By 1808, Astor had established "an international empire that mixed furs, teas, and silks and penetrated markets on three continents."[8] He began to court diplomatic and government support of a fur trading venture to be established on the Pacific shore in the same year. In correspondence with the Mayor of New York City, DeWitt Clinton, Astor explained that a state charter would offer a particular level of formal sanction needed in the venture.[3] He in turn requested the Federal government grant his operations military support to defend against British citizens and control these new markets. The bold proposals were not given official sanction however, making Astor to continue to promote his ideas among prominent governmental agents.

President Thomas Jefferson was contacted by the ambitious merchant as well. Astor gave a detailed plan of his mercantile considerations, declaring that they were designed to bring about American commercial dominance over "the greater part of the fur-trade of this continent..."[3] This was to be accomplished through a chain of interconnected trading posts that stretching across the Great Lakes, the Missouri River basin, the Rocky Mountains, and ending with a fort at the entrance of the Columbia River.[9] Once the pelts were collected from the extensive outposts they were to be loaded and shipped aboard ships owned by Astor to the Chinese port of Guangzhou, where furs were sold for impressive profits. Chinese products like porcelain, nankeens and tea were to be purchased; with the ships then to cross the Indian Ocean and head for European and American markets to sell the Chinese wares.[10]

SubsidiariesEdit

Pacific Fur CompanyEdit

To begin his plans of a chain of trading stations spread across the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Northwest, Astor incorporated the AFC subsidiary, the Pacific Fur Company.[11][12] Astor and the partners met in New York on 23 June 1810 and signed the Pacific Fur Company's provisional agreement.[13] The fellow partners were former NWC men, being Alexander McKay, Duncan McDougall, and Donald Mackenzie. The chief representative of Astor in the daily operations was Wilson Price Hunt, a St. Louis businessman with no outback experience.[12]

From the outpost on the Columbia, Astor hoped to gain a commercial foothold in Russian America and China.[10] In particular, the ongoing supply issues faced by the Russian-American Company were seen as a means to gain yet more furs.[14] Cargo ships en route from the Columbia were planned to then sail north for Russian America to bring much needed provisions.[10] By cooperating with Russian colonial authorities to strengthen their material presence in Russian America, it was hoped by Astor to stop the NWC or any other British presence to be established upon the Pacific Coast.[2] A tentative agreement for merchant vessels owned by Astor to ship furs gathered in Russian America into the Qing Empire was signed in 1812.[14]

While intended to gain control of the regional fur trade, the Pacific Fur Company floundered in the War of 1812. The threat of military occupation by the British Navy forced the sale of all company assets across the Oregon Country. This was formalized on 23 October 1813 with the raising of the Union Jack at Fort Astoria.[15] On 30 November HMS Racoon arrived at the Columbia River and in honor of George III of the United Kingdom, Fort Astoria was renamed Fort George.[16] After the forced merger in 1821 of the North West Company into their long time rivals, the Hudson's Bay Company, in a short time the HBC controlled the majority of the fur trade across the Pacific Northwest. This was done in a manner that "the Americans were forced to acknowledge that Astor's dream" of a multi-continent economic web "had been realized... by his enterprising and far-sighted competitors."[17]

South West CompanyEdit

The South West Company handled the Midwestern fur trade. In the Midwest, it also competed with regional companies along the upper Missouri, upper Mississippi and Platte rivers, especially companies based in Saint Louis, Missouri, which was based on the fur trade of major French colonial families before the Louisiana Purchase or Astor setting up his company. Competition in the wilderness areas between men of the companies erupted into physical violence and outright attacks.

Later historyEdit

For a time, it seemed that the company had been destroyed but, following the war, the United States passed a law excluding foreign traders from operating on U.S. territory. This freed the American Fur Company from having to compete with the Canadian and British companies, particularly along the borders around the Great Lakes and in the West. The AFC competed fiercely among American companies to establish a monopoly in the Great Lakes region and the Midwest. In the 1820s the AFC expanded its monopoly into the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains, dominating the fur trade in what became Montana by the mid-1830s.[18] To achieve control of the industry, the company bought out or beat out many smaller competitors, like the Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

By 1830, the AFC had nearly complete control of the fur trade in the United States. The company's time at the top of America's business world was short-lived. Sensing the eventual decline of fur's popularity in fashion, John Jacob Astor withdrew from the company in 1834. The company split into smaller entities like the Pacific Fur Company. The midwestern outfit continued to be called the American Fur Company and was led by Ramsay Crooks. To cut down on expenses, it began closing many of its trading posts.

DeclineEdit

Through the 1830s, competition began to resurface. At the same time, the availability of furs in the Midwest declined. During this period, the Hudson's Bay Company began an effort to destroy the American fur companies from its Columbia District headquarters at Fort Vancouver. By depleting furs in the Snake River country and underselling the American Fur Company at the annual Rocky Mountain Rendezvous, the HBC effectively ruined American fur trading efforts in the Rocky Mountains.[19] By the 1840s, silk was replacing fur for hats as the clothing fashion in Europe. The company was unable to cope with all these factors. Despite efforts to increase profits by diversifying into other industries like lead mining, the American Fur Company folded. The assets of the company were split into several smaller operations, most of which failed by the 1850s. In 1834, John Jacob Astor sold his interest on the river to replace the old fur company. He invested his fortune in real estate on Manhattan Island, New York, and became the wealthiest man in America. After 1840, the business of the American Fur Company declined.

InfluenceEdit

During its heyday, the American Fur Company was one of the largest enterprises in the United States and held a total monopoly of the lucrative fur trade in the young nation by the 1820s. Through his profits from the company, John Jacob Astor made numerous, lucrative land investments and became the richest man in the world and the first multi-millionaire in the United States.

The German-born Astor is ranked as the eighteenth-wealthiest person of all time, and the eighth to create his fortune in the United States. He used part of his fortune to found the Astor Library in New York City. Later it merged with the Lenox Library to form the New York Public Library.

On the frontier, the American Fur Company opened the way for the settlement and economic development of the Midwestern and Western United States. Mountain men working for the company improved Native American trails and carved others that led settlers into the West. Many cities in the Midwest and West, such as Fort Benton, Montana, and Astoria, Oregon developed around American Fur Company trading posts. The company played a major role in the development and expansion of the young United States.

See alsoEdit

References

- Ingham 1983, pp. 26-27.

- ^ a b Tikhmenev 1978, pp. 116-118.

- ^ a b c d Rhonda 1986.

- ^ a b Chapin 2014, pp. 231-232.

- ^ a b MacKenzie 1802.

- ^ a b Porter 1931, p. 170.

- Haeger 1988, p. 188.

- ^ a b Haeger 1988, p. 189.

- Haeger 1988, p. 190.

- ^ a b c Chittenden 1902, p. 167.

- Chittenden 1902, p. 168.

- ^ a b Ross 1849, pp. 7-10.

- Irving 1836, pp. 26-27.

- ^ a b Wheeler 1971.

- Franchère 1854, pp. 190-193.

- Franchère 1854, pp. 200-201.

- Tikhmenev 1978, p. 169.

- Malone 1991, pp. 54–56.

- Mackie 1997, pp. 107-111.

Bibliography

- Chapin, David (2014), Freshwater Passages, the Trade and Travels of Peter Pond, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-4632-4

- Chittenden, Hiram Martin (1902), The American Fur Trade of the Far West, New York: Francis P. Harper

- Franchère, Gabriel (1854), Narrative of a voyage to the Northwest coast of America, in the years 1811, 1812, 1813, and 1814, translated by Huntington, J. V., New York City: Redfield

- Haeger, John D. (1988), "Business Strategy and Practice in the Early Republic: John Jacob Astor and the American Fur Trade", Western Historical Quarterly, Logan, UT: Western Historical Quarterly, 19 (2): 183–202

- Ingham, John M. (1983), Biographical dictionary of American business leaders, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-23907-X

- Irving, Washington (1836), Astoria, Paris: Baudry's European Library

- Mackie, Richard Somerset (1997), Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific 1793-1843, Vancouver: University of British Columbia (UBC) Press, ISBN 0-7748-0613-3

- Malone, Michael P.; Roeder, Richard B.; Lang, William L. (1991), Montana : a history of two centuries (Revised ed.), Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press

- Porter, Kenneth W. (1931), John Jacob Astor: Business Man, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- Ross, Alexander (1849), Adventures of the first settlers on the Oregon or Columbia River, London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Tikhmenev, P. A. (1978), A History of the Russian-American Company, translated by Pierce, Richard A.; Donnelly, Alton S., Seattle: University of Washington Press

- Wheeler, Mary E. (1971), "Empires in Conflict and Cooperation: The "Bostonians" and the Russian-American Company", Pacific Historical Review, Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 40 (4): 419–441