Friday, May 18, 2018

Sounds familiar :)

Monday, May 14, 2018

Global history: how to use ice in Greenland to tell the history of the Roman Empire’s economy

An Ice Core Reveals the Economic Health of the Roman Empire

Sunday, May 13, 2018

Apropos the last lecture, some interesting newspaper headlines from a typical American paper in the summer and fall of 1941

Thursday, May 10, 2018

An amazing story from a survivor of the 1st global economy, written down in the 1920s

The story of one of the last slaves imported to America

Zora Neale Hurston's devastating "Barracoon" is finally being published

Zora Neale Hurston's devastating "Barracoon" is finally being published

Barracoon: The Story of the Last. By Zora Neale Hurston. Amistad; 208 pages; $24.99. HQ; £12.99.

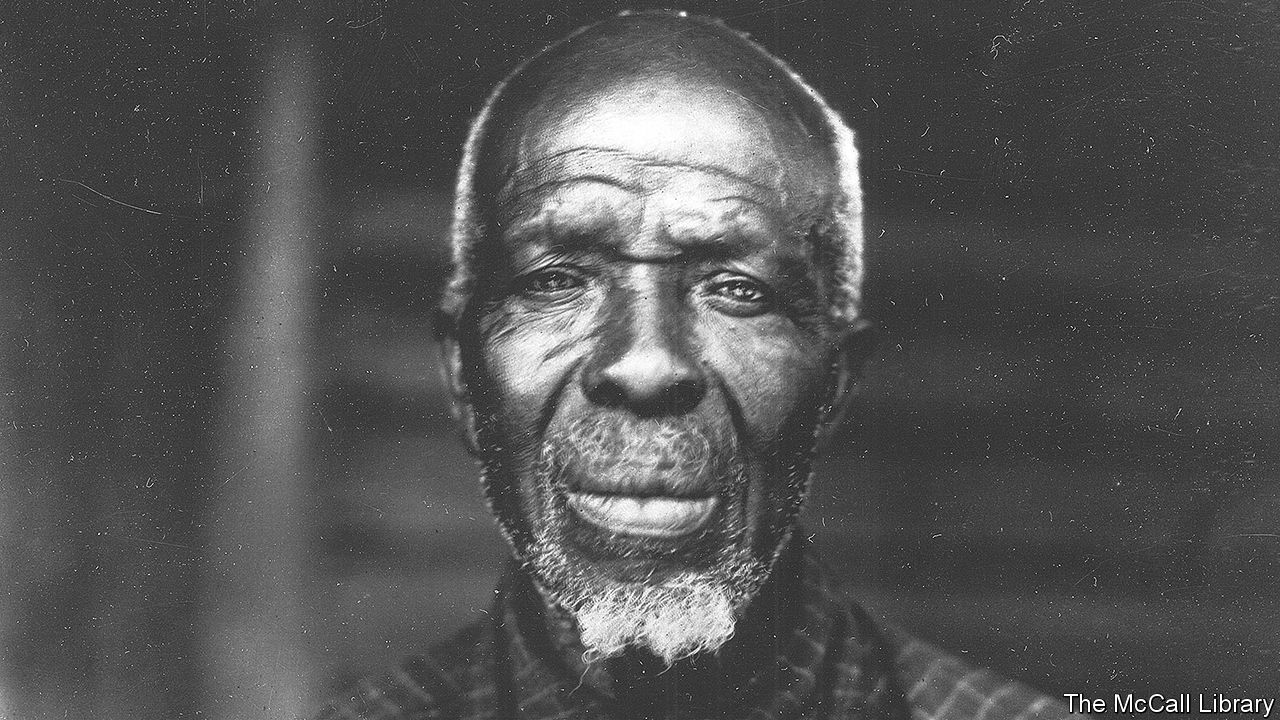

MOBILE, Alabama, lies at the raggedy end of the American mainland, amid a boggy landscape of swamp and forest where five rivers empty into the sea. The air smells green, and secrets lurk in the creeks, rills and tree-shrouded coves. Buried somewhere in the muck of Mobile Bay is the burned wreck of the Clotilda—the last ship known to have brought slaves from Africa to America.

One of those slaves was named Kossula in Africa, but became Cudjo Lewis in Alabama. Over three months in late 1927 and early 1928 he was interviewed at his home by Zora Neale Hurston, who later won acclaim as a novelist. Cudjo was among the last survivors of the Clotilda, and thus among the last living Americans to have been transported as a slave. Hurston described their encounters and his life in a book, "Barracoon". The name refers to the barracks in which captives were kept before their buyers took possession of them.

"Barracoon" is now being published for the first time. How it came to languish for decades in an archive, and its place in Hurston's embattled writing career, are interesting stories in themselves. Because of its extraordinary circumstances, Cudjo's own story is highly unusual among accounts of American slavery. It is also heartbreaking.

Grief so heavy

Almost all American slave narratives were composed by people born in the country, and thus contain no first-hand recollections of capture and transportation. Cudjo, who was enslaved as a teenager in 1859, recalls the calamity vividly.

In his and Hurston's telling, soldiers from the Kingdom of Dahomey (present-day Benin) surround his town, beheading some prisoners, preserving others to sell. On the march to Dahomey he watches the murder of his king; he sees the soldiers smoking the heads of his countrymen. He calls out for his parents but—in a dialect that Hurston transcribes—he remembers that "de soldiers say dey got no ears for cryin'." As he recounts the forced march, he falls silent. He "was no longer on the porch with me," Hurston writes. "He was squatting about that fire in Dahomey…gazing into the dead faces in the smoke."

After the raid Cudjo's captors bring him to Ouidah, a town on the coast from which hundreds of thousands left in chains. There he sees white men and the ocean for the first time. He boards the Clotilda with victims from several other nations. After nearly two weeks at sea he is brought above decks: "We doan see nothin' but water. Where we come from we doan know. Where we goin we doan know."

The voyage took 70 days. Bill Foster, the Clotilda's captain, scuttled her in Mobile Bay because in 1860, when she returned with her human cargo, importing slaves had been illegal for 52 years, and was theoretically punishable by hanging. Timothy Meaher, a prominent businessman, had reputedly bet that he could defy the ban, and financed the journey and the purchase. But federal officials got wind of the scheme, so on their return Foster towed the Clotilda up Mobile Bay in the dead of night, offloaded the 110 captives aboard onto a steamer, and torched the ship.

After they are smuggled into America, the Africans are separated again. "We cain help but cry…Our grief so heavy look lak we cain stand it. I think maybe I die in my sleep when I dream about my mama. Oh Lor'!" They joined the more than 45% of Alabama's population who were enslaved.

Upon emancipation in 1865, at the end of the civil war, some of the slaves who have been pressed into the Meaher family's service ask for land in recompense for their bondage. "Fool," Meaher replies in "Barracoon"; "do you think I goin' give you property on top of property?" So they pool their money and buy a plot of land. "We call our village Affican Town," Cudjo explains, "'cause we want to go back in de Affica soil and we see we cain go. Derefo' we makee de Affica where dey fetch us."

Africatown was among the hundreds of settlements across the South founded by freed slaves after the civil war. Hurston herself grew up in another (Eatonville, Florida). But it was the only one established by Africans, with living memories of their homeland, memories that haunt Cudjo and make "Barracoon" a devastating document of suffering and cruelty.

His trials continue after he is freed. He loses his daughter and all five of his sons. One is killed by a deputy sheriff, another by a train. His wife dies, too. He mentions his loneliness often, and sees Hurston as a lifeline to the wider world: "I want tellee somebody who I is, so maybe dey go in de Afficky soil some day and callee my name and somebody dere say, 'Yeah, I know Kossula'." On one of her last visits she asks to photograph him. Cudjo emerges from his house in his best suit, without shoes. "I want to look lak I in Affica," he says, "'cause dat where I want to be."

Hurston submitted "Barracoon" to publishers in 1931. Two rejected it, and she withdrew it from a third, who asked that she rewrite Cudjo's dialect. She declined, and the manuscript was put aside. But dialect was an essential element of all Hurston's work. She trained as an ethnographer before embarking on a literary career, and was a first-rate listener who revelled in her subjects' natural cadences. In Cudjo, himself a gifted storyteller and crafter of parables, she found an ideal interlocutor.

Not one word from the sold

There were some doubts—not unusual for biographies—about how much of "Barracoon" was Cudjo's story and how much Hurston's (a short article she had written about him earlier showed signs of plagiarism). She also drew criticism from her peers in the Harlem Renaissance because of her aversion to politics, particularly from Richard Wright, author of "Native Son" and at the time a dedicated communist. But in "Barracoon", as in "Their Eyes Were Watching God", a humane novel of black life in Florida that she published in 1937, her neutrality serves her well. It puts Cudjo's voice, rather than her views, at the book's heart. That was the point: "Of all the millions transported from Africa, only one man is left," Hurston writes in her introduction. "All these words from the seller, but not one from the sold."

Although Hurston continued writing and travelling throughout the 1930s and 1940s, her star waned. In 1950 she took a job as a maid in Miami. Ten years later she died and was buried in an unmarked grave. The writer Alice Walker began to restore her reputation in the mid-1970s; today "Their Eyes Were Watching God" is a mainstay of America's school curriculum. "Barracoon" may belatedly become one as well.

For his part, Timothy Meaher escaped serious punishment for his crime. His family remained prominent in south Alabama. At the northern shore of Mobile Bay, in the vicinity of the Clotilda's likely resting place, is Meaher State Park, named after a relative of the slaver.

As for Africatown, these days it is a proud but poor part of northern Mobile. The city annexed it in the 1950s, after two paper mills were built there, generating both tax revenue and toxic sludge. A neighbourhood called Lewis Quarters still runs between two lumberyards, leading to the Lewis homestead. Local legend says that the lumber firms tried to buy the family out, but they refused to leave.

Down a narrow side street stands the school that Cudjo founded; his family's memorabilia sit in a private museum inside. Along bustling Africatown Road is the Baptist church he helped establish, which still throngs with worshippers on Sundays and has a bust of him out front.

Across the street is the modest graveyard where he and the other stolen Africans are buried. On Cudjo's memorial stone visitors routinely place heads-up dimes, which locals hint has something to do with the Yoruba religion. The headstones on the Africans' graves face east, looking toward a homeland they never returned to, and never forgot.

Wednesday, May 9, 2018

The China Ship

The discovery of the roundtrip and the beginning of globalisation

May 6, 2018

The China Ship

chapter 1

The China Ship

By Adolfo Arranz & Marco Hernandez

chapter 1

By Adolfo

Arranz

Marco

Hernandez Globalisation is thought to have its beginnings in the 16th century when the Spanish silver dollar went transcontinental. Its acceptance as common currency arose when Spanish navigators in the Philippines established a circular shipping route, known as the tornaviaje, between Asia and the Americas. More than 250 years of uninterrupted trade ensued between Asia and the rest of the world. And the ships plying this route were known as China Ships

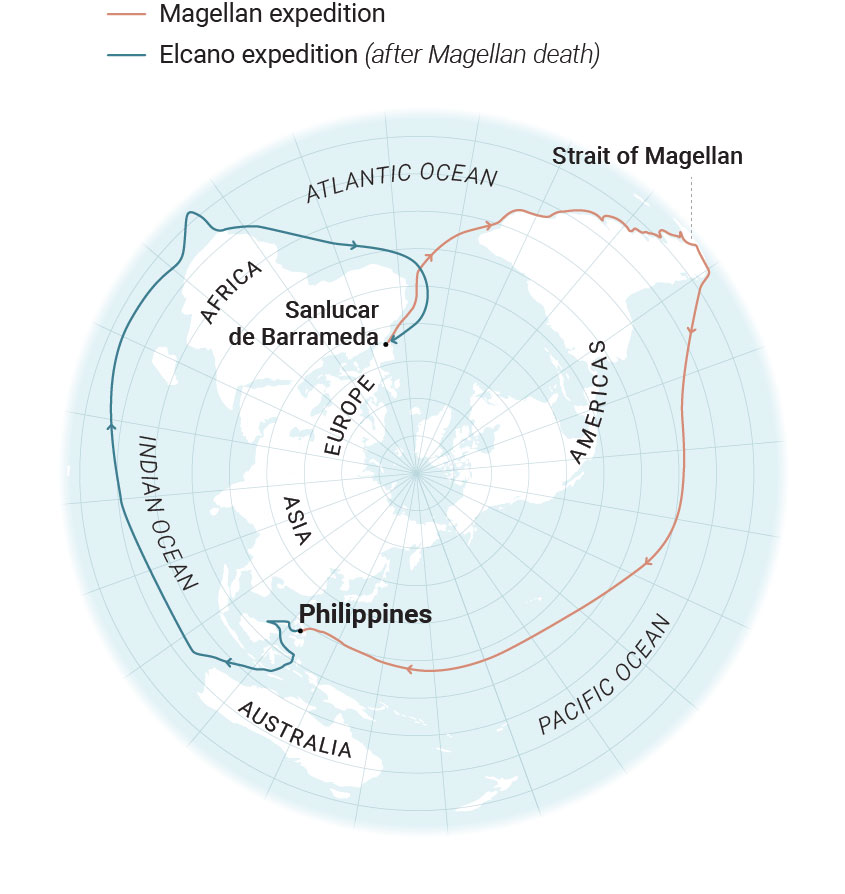

Magellan-Elcano circumnavigation

In 1519 a Spanish fleet of five vessels, under the command of Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, set sail from Seville in search of a route across the Pacific Ocean to East Asia. Magellan was killed in a battle during the voyage, leaving Spanish navigator Juan Sebastian Elcano and 18 surviving crew to become the first to circumnavigate the globe in a single expedition. Their expedition finally returned home to Spain in 1522

Magellan's arrival in the Philippine Archipelago on March 15, 1521 was the first encounter between Spaniards and the people of the Philippines

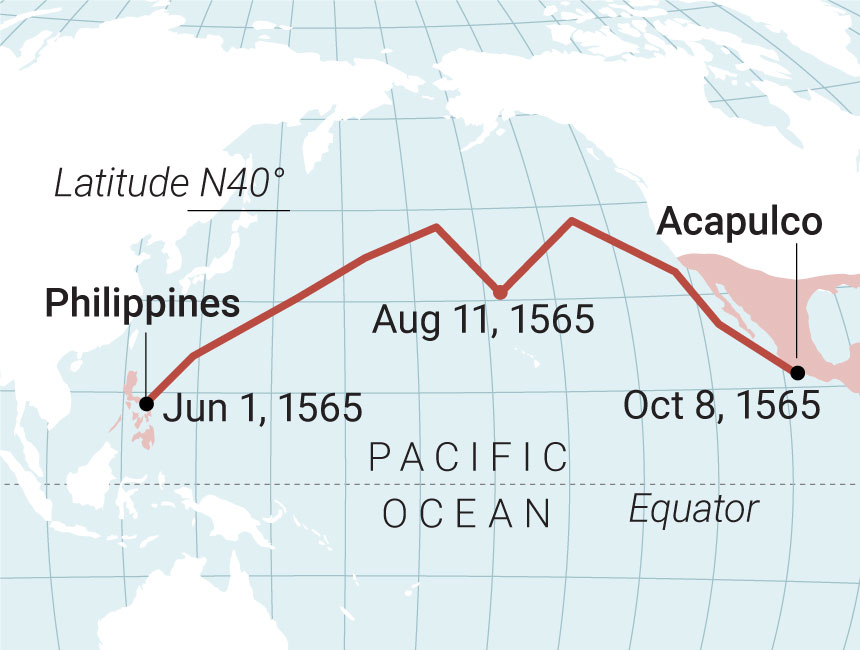

The tornaviaje discovery

Between 1526 and 1540, Spain sent two more expeditions to the Philippines, but neither completed the return journey to the Americas. A fourth expedition, led by Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, arrived in the Philippines in 1565. While many of the crew settled on the islands, one sailor named Andres de Urdaneta had a very important job to do

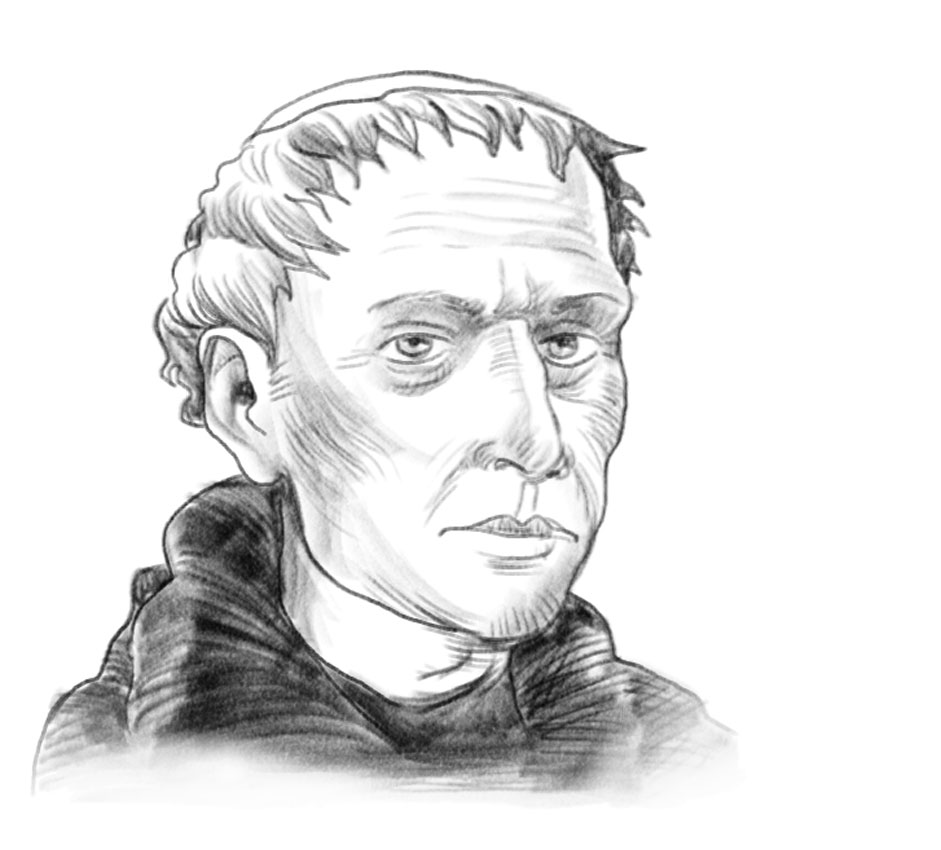

Andres de Urdaneta

(1498-1568)

Andres de Urdaneta was commissioned by King Philip II to lead an expedition back to New Spain as soon as possible, plot the return passage and establish trade routes across the Pacific Ocean

An Augustinian friar, sailor and author, Urdaneta would become one of the Pacific Ocean's most knowledgeable European navigators. He sailed north, crossing the Pacific near 40°N latitude, arrived in Acapulco 130 days later from Cebu. From there, he discovered a return maritime route to the Americas and, more significantly, kept records and navigation charts of his odyssey

Because of his efforts, the world's longest maritime route was established. It would endure for 250 years

The round trip

Manila was ideally located for a major trading port of Chinese goods, such as silk and tea –which were highly coveted in Europe and America. Keeping pace with the trade boom, Manila's Chinese community grew exponentially. And as traders hustled, sailors got much-needed rest before the arduous journey to Acapulco, Mexico, where Spanish galleons traded their exotic goods for silver coins

SHIPPING COMPLETION TIME

The longest regular shipping line: 250 years

In terms of operating years and distances covered, the tornaviaje was the longest regular shipping line in history. This table estimates the number of ships that made the voyage and whether they survived

Stay tuned for the second chapter

"Galleon of China: flagship of trade over two centuries"

Coming up week, discover how was built the China Ship and explore it deeply in detail

Enjoying South China Morning Post graphics?

Here are some other digital native projects you might want to visit

Or just visit our graphics home page